Re-Embodying Through Art: From Cosplay to Cartographies of the Self

We leave our bodies all the time.

Not in the grand sci-fi astral-projection way (though, let’s be honest, some days that would be easier)—but in the slow, subtle, dissociative drift that happens when life pulls too hard. Trauma does this. Social media does this. The nonstop feed of stress, expectation, and pixelated realities turns the body into something secondary, something inconvenient. We move through the world like floating heads, disconnected from breath, from skin, from the sheer weight of being alive.

Chantal Akerman’s films captured this disembodiment—the long, empty corridors, the sterile repetitions of domestic life, the feeling that space itself had swallowed us whole. It’s not just the architecture; it’s the psychology of it. The way modern life flattens us into something less than whole.

But what if we could get back in?

COSPLAY, ART, AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF SELF

This is where cosplay comes in. This is where art comes in.

To embody something is to step into a form with intention. It’s what happens when a cosplayer puts on armor, when fabric and foam become exoskeleton, when an idea takes shape inside a person. The body is no longer an afterthought—it’s the main event. The place where transformation occurs.

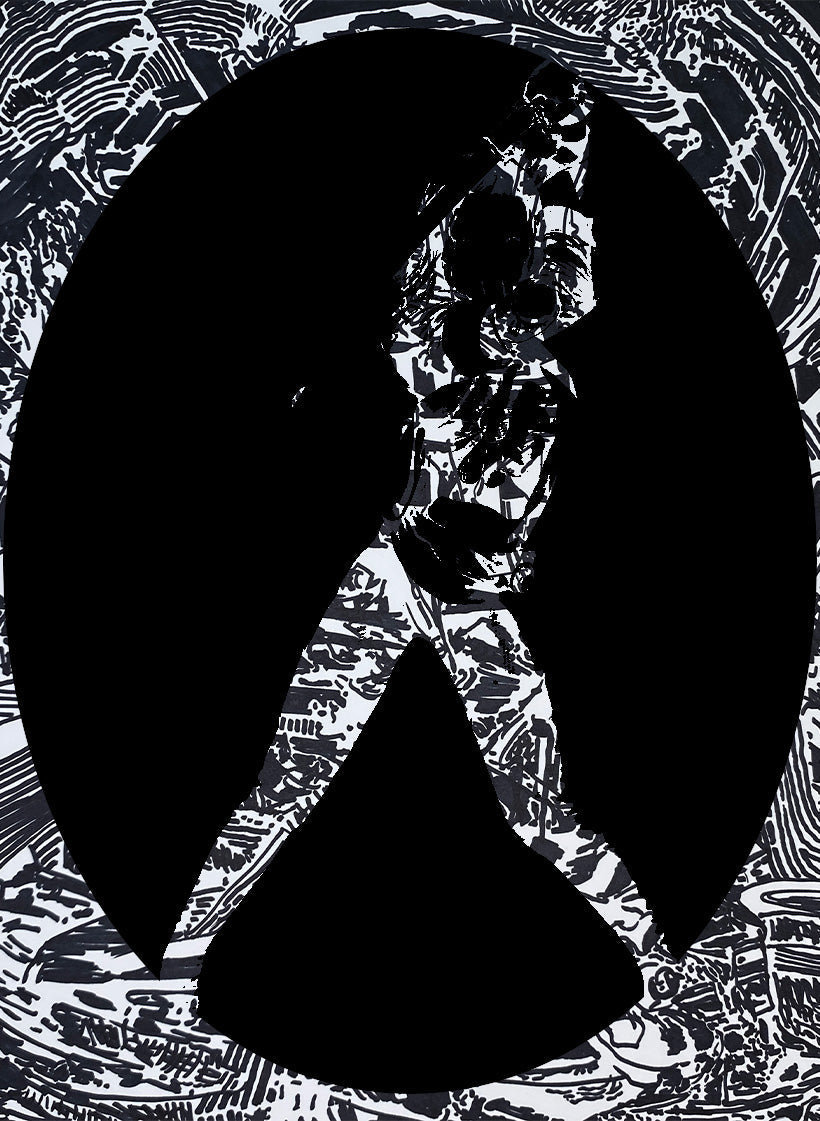

Works of art function the same way. Throughout history, they have acted as sites of presence, grounding viewers in something beyond themselves. Abstract compositions, in particular, have long served as visual records—not just of external landscapes, but of the internal, the energetic, the ephemeral. Art creates a space to inhabit, a terrain that mirrors what has been felt, remembered, or imagined.

Some drawings exist as maps—cartographies of experience that capture the way life moves through us. These maps do not follow the logic of streets and borders; they follow the invisible contours of thought, sensation, and interaction. They help synthesize large, complex systems, bringing them into focus, offering clarity where there was once only chaos.

Cosplay, gameplay, both allow us to enter and experience spaces akin to modern life's kaleidoscope of daily perceptions—a great comfort, validation and acknowledgement of what we go through every minute of everyday in a souped up version of existence. Having a record such as these drawings to later reflect on what we are feeling in those spaces can reconnect and re-embody us.

And we don't necessarily need to make the work, even the simple act of observation holds power. Cornell Medical research found that doctors trained in slow, deliberate art observation became significantly better at diagnosing medical conditions. The mind, when taught to look with attention, gains an ability to see more clearly—not just in a gallery, but in life itself.

RE-EMBODYING THROUGH OBSERVATION & CREATION

Arianna Huffington’s wellness research emphasizes micro-adjustments—small, intentional practices that bring people back into their bodies. Art is one of them. Observing art. Making art. Allowing it to act as an anchor, pulling attention away from the external noise and into a place of presence.

It becomes a reversal of Akerman’s disembodied spaces: instead of drifting in blank, dissociative environments, we root ourselves in landscapes of meaning. Instead of disappearing into the endless scroll, we step inside something deliberate. My students have consistently said, for 32 years, they can't find the time to make more time. So the deliberate became something I worked to offer in 1 minute exercises to connect: to self, to the moment, to current thought, to imagination, to nature, to meaning, and I have seen the evidence of their settling due to this deliberate connecting.

There is also something uniquely powerful in art that records movement and thought. These works are unique spaces—ones that can be entered, studied, felt—ones that invite the (maybe) long unimaginable space of freedom, of youthful forgiveness, back into our mind/body. They allow for a kind of recognition, a way of seeing one’s own current experiences reflected back in shape, color, rhythm. They function as guides, offering a sense of orientation in the vastness of the unknown, albeit through a lens of the otherworldly. ("Such fun!" Miranda's mom. Yes, it can be challenging too while simultaneously rewarding.)

Art, particularly abstract art, functions as a kind of perceptual training ground. It demands a particular kind of attention—not the quick, grasping gaze of consumer culture, or the literal nouns of language, but a slower, embodied way of seeing. Alva Noë has suggested that artistic practices are “strange tools”—not just reflections of the world, but active interventions in how we perceive and engage with it. The spaces created by art aren’t static images; they are experiences, ones that can be entered, studied, felt.

Whether through cosplay, drawing, or simply the act of paying close attention, there is a path back into the body. A way to re-inhabit oneself. A way to return.

And art, in all its forms, is waiting.